-min.png?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&rect=160%2C0%2C4534%2C3023&w=2500&h=1667)

The Truth about DRT

Demand-responsive transit isn’t a niche, binary, or new solution.

By Dami Adebayo, Partnerships Lead — Europe

Out of all the types of passenger transport available today, Demand Responsive Transport (or “DRT”) might just be the one with the most broad definition. Truth be told, the name DRT itself can be a double-edged sword: it’s an all-encompassing term which sums up the versatility of it as a service type, but it's not exactly the most catchy acronym. Even when spelled out in full, it's unlikely you’re familiar with the concept unless you’re a transport professional or enthusiast.

Perhaps you’ve heard of on-demand transport, microtransit, paratransit, flexible buses, dial-a-ride, smart shuttles, ridepooling, or vanpooling? These are all different names for services which can fall under the umbrella of Demand Responsive Transport.

They can be best described as flexible transport services which live at the intersection of taxi and conventional bus services. Like taxis, one can book a DRT journey using an app or call centre (either on-demand or in advance) to pick you up and take you to your desired destination. But like buses, the vehicles are supposed to be shared with other passengers going in similar directions.

Over the last 2 years, I’ve attended or presented at various mobility conferences where I’ve noticed a worrying trend: regardless of the name used, DRT is often falsely introduced as:

- a new solution,

- a niche solution; or

- a binary solution.

These misconceptions can be detrimental to the success of DRT services before they begin — here’s why they’re wrong, and how addressing them will lead to better solutions.

Demand-responsive transport is not new.

The concept of DRT has existed for centuries in the form of informal community-based arrangements, and the first formal DRT services likely emerged in the 1960s as ‘dial-a-ride’ services. Since then, DRT has been a vital form of transport, primarily for marginalised communities, all around the world.

What's new today is the technology used to deliver these services. This shift is similar to the disruption of the taxi industry by ride-hailing tech companies circa 2009. In the UK, “Digital DRT” (or “DDRT”) is becoming the recognised term for demand-responsive transport solutions delivered using advanced technology and mobile apps. But unlike the ride-hailing shift, where the app itself was the radical change, a DDRT app is simply a vessel for the true innovation: the use of intelligent algorithms that can rapidly create efficient routes & schedules, shared between multiple passengers who are looking to book different journeys.

These algorithms empower modern DRT services to accept more total bookings with the benefit that those bookings can be on-demand (in real time), rather than requiring that trips are requested well in advance. It takes the core principle of what public transport does really well — putting multiple passengers in shared vehicles — and applies it to DRT. And, while bookings can indeed be made through an app, they can also still be made through call centres, as has been the case in traditional DRT services.

So, what does this mean for operators?

When developing new DDRT offerings, the focus should not be all the things an app can do, but how that app’s engine — its algorithm — can assess, account for, and adjust to the unique ways and times that people in communities travel. Why? Because the real-time routing of demand-responsive vehicles is what ultimately dictates the end-user experience, service accessibility, vehicle emissions and operational costs.

Demand-responsive transport is not a niche solution.

DRT has historically been used in rural settings, where population density is low and there are few other public transport options, or for passengers with reduced mobility who find it difficult to access conventional public transport services. As a result, traditional DRT services are often seen as niche, given they cater towards a relatively small volume of people when compared to other public transport options.

This is exacerbated by the fact that DRT is often designed in a silo — as a standalone service which caters to a very specific area or subset of users. But technological advancements are making it easier for DRT services to be better integrated across all types of rural or urban communities.

According to CoMoUK’s 2023 DDRT Report, almost half of DDRT schemes were implemented to feed into or supplement pre-existing services. This is delivered by intelligently configuring DRT pick ups and drop offs in line with the schedules of other public transport modes. Users in urban areas can benefit from DRT as a first/last-mile feeder service which provides connectivity to their nearest bus/rail station, thus extending the coverage of public transport networks beyond trunk routes. Our Pingo platform’s Transit Connect™ feature does exactly this, and has a 99% success rate in dropping passengers off in time to reach their onward journey.

Another use case: privately-run shared shuttle services, such as those provided by a large employer to simplify commutes and enhance access to their facilities. Shared shuttles can be especially effective at changing mobility behaviour, as private companies are able to more substantially subsidise and promote these services to encourage their employees to use cars less. Whilst company cars have become a common employee benefit, a BVRLA survey in 2020 reported that 24% of company car drivers in the UK suggested their car was not essential for their job. Employers with large commuting workforces should consider offering demand responsive shuttles as an effective way to lower carbon emissions whilst still providing a convenient transport benefit to their employees.

Demand-responsive transport is not a binary solution — there’s an entire spectrum of possibilities.

The most detrimental roadblock to a DRT service’s success, perhaps, is when service planners design a service based solely on the singular type of DRT configuration they have been exposed to.

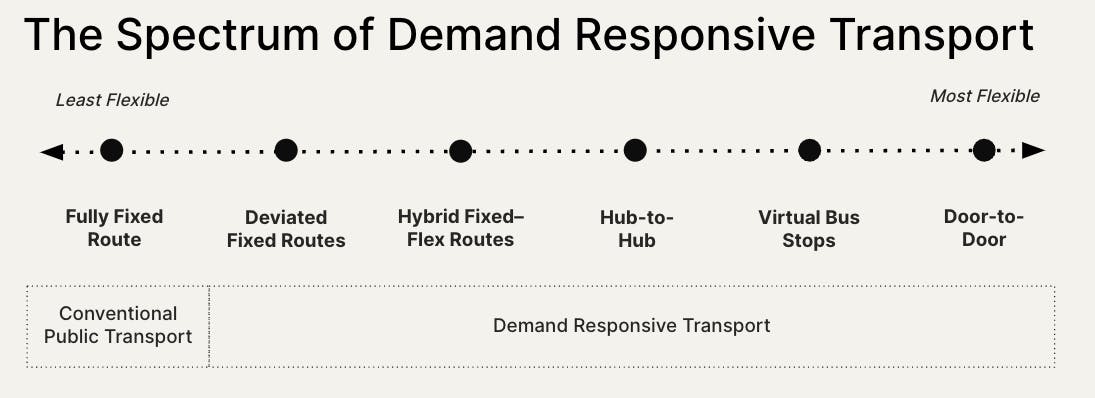

It may seem straightforward to classify a 'conventional' bus and a DRT bus into two binary categories: the former runs on a fixed schedule, and the latter flexibly operates without a schedule (thus, it seems “binary” in nature). In reality, this limits the possibilities. There are so many ways to configure and deliver demand-responsive transport — DRT can encompass a spectrum of solutions that vary in flexibility and can include scheduled elements:

Door-to-door services are the most flexible type of DRT, as they allow passengers to receive direct point-to-point transportation to their desired pick-up and drop-off locations anywhere within a zone.

Virtual bus stops allow passengers to be picked up and dropped off at designated locations only. Stops are predefined by the provider and typically do not exceed a maximum walking distance.

Hub-to-hub services operate between fixed points of interest only (e.g., major transport stations, metropolitan centres). They could also be made more flexible to be point-to-hub or hub-to-point services for certain geographical areas or communities.

Hybrid fixed-flex routes offer a combination of fixed routes with set schedules (e.g., during peak hours), but with flexible on-demand services outside of those times (e.g., off peak hours). These hybrid services can also vary in flexibility based on certain subsets of an operating zone.

Deviated fixed routes are the least flexible type of DRT — a vehicle follows a fixed route, but is able to make small deviations from the route to pick or drop passengers beyond the bus stop.

Two key factors to consider in selecting any of these types of DRT services:

(i) fleet availability in terms of the number and capacity of vehicles available for the service; and

(ii) user and non-user demand in terms of people’s current disposition and future likelihood to make use of the different elements of each DRT service type.

How can you better integrate DRT in future?

Too often, a decision on which type of DRT service to deploy is made prematurely based on the planning entity’s prior experiences, without truly taking into account the most important stakeholders: the end-users.

Transport authorities, operators and tech providers must collaborate to think holistically about how a DRT service should be designed and delivered. All these parties bring unique insights which ultimately benefit the end user and will allow us to unlock the full potential of DRT going forward. To achieve this, it is integral to factor in the full spectrum of DRT, how it can effectively complement or integrate with nearby public transport services, as well as how it can improve the operational efficiencies of any existing similar services.

And no matter how exhaustive the planning of a DRT service is, the truth is that design of a DRT solution should never be considered truly final. Having supported the roll-out of several new services across the UK and the Netherlands, I’ve remained involved in the ongoing evolution - and that’s exactly how it should be. It is not only the vehicle routes that are “demand responsive”; there must be a willingness to make iterative scope and design alterations to ensure the solution continues to serve demands which will naturally change over time.

Dami Adebayo is the Partnerships Lead, Europe at The Routing Company (“TRC”). TRC provides flexible, efficient, and convenient transit through on-demand, fixed, flex, or commingled paratransit shared transportation. Founded by MIT researchers and rideshare industry veterans, TRC is a global on-demand vehicle routing and management platform that partners with cities to power the future of public transit, while enabling greater transit equity, accessibility, cost efficiency, and sustainability. Learn more at theroutingcompany.com or contact dami@theroutingcompany.com.